Who is afraid of progress?

I sit down at the end of the day and open my notebook, a fountain pen in hand with the ink I feel like using that evening (a soft, purple-leaning grey), and write about what I have been doing, how I have been feeling, what I have been (and now, am) thinking. The paper is very thin and soft to the touch, a muted white with very thin lines conforming a grid. The nib of the pen glides on the surface, needing nearly no pressure to draw squiggles that speak through my fingers all the way from my brain. I adjust the angle of the notebook as I keep writing, resting on it, holding it in between my hands with my eyes focusing on the page or lifting off and getting lost through the window, temporarily caught in a loop of exploration and translation of thoughts into words.

The ritual is complete when I reach the end of the page; I could write more or I could write less, but I limit myself to what the space of the sheet affords me. I don't think along the lines of "how much should I write today" but, rather, I sit down and allow myself to just start: writing the first sentence that comes to mind; seeing where it leads me. That way, one word at a time, I fill out a page here and a page there, not so much so I can re-read it later on, but so that I can think through something, anything, away from everything else at that moment in time - so I can connect with my own self and my own thoughts. Writing on my notebook slows things down: I take my time moving my pen on the paper; I can smell the ink, I can feel the notebook widely open between my hands (the rougher pages I have already written on, the crisp pages that remain blank), and I can see at a glance how far in the notebook I've gone: how far I've come, and how far I can still go.

There is no inherently instrumental reason as to why I sometimes write on notebooks that could be easily linked to the concepts of productivity and efficiency, or to the idea of what is "most optimal" or "better"; it is a different experience altogether, an experience which includes specific haptics, constructive limits, and unstructured possibilities, a multi-sensory experience that writing on a keyboard could never afford me.

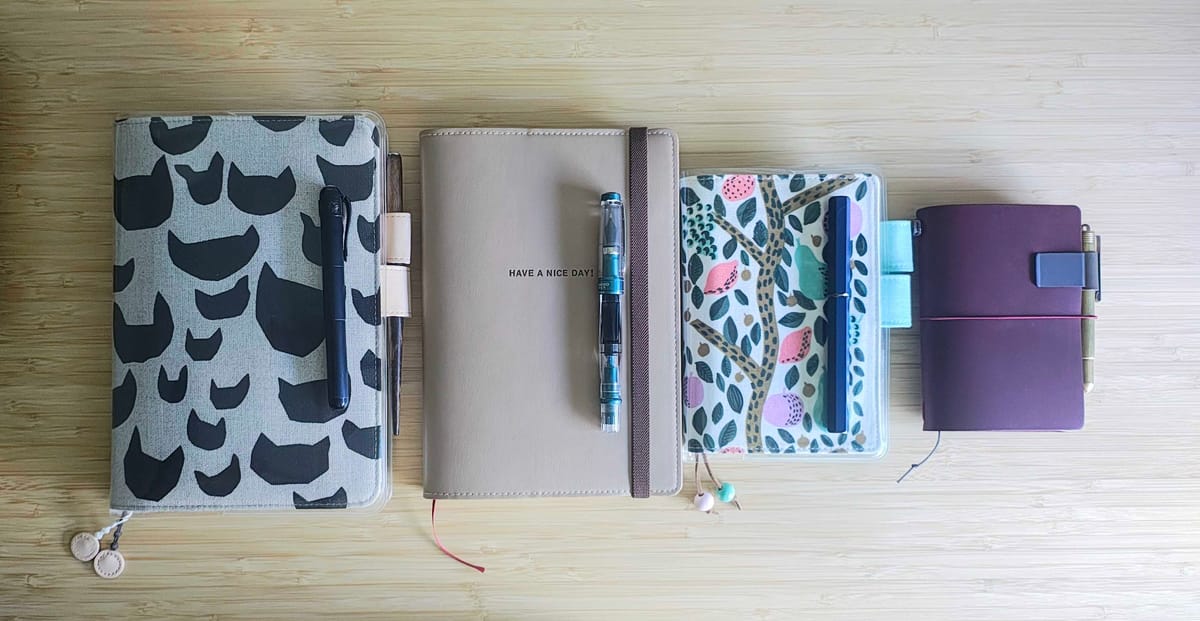

I bring a notebook with me when I go out to sit at a café, my goal being to just take a moment off to think, ponder, and have a dialogue with myself. I also have a notebook that I use for work - I note things down that I have read, I draft ideas, I take notes at some meetings, I devise to-do lists and keep track of projects. I use memo cards to have at hand during online meetings so I can quickly write down things I should check or remember. But I do not use notebooks for everything. In fact, I'm writing this on my laptop after having written a rough bullet-point draft on my phone. I use a variety of tools to different aims and purposes, and for a variety of reasons. None of these tools is "the best tool"; none of them is the "most advanced" tool either.

In fact, even something as seemingly rudimentary as paper is subject to progress and innovation - new techniques are devised to, for example, reduce paper thickness while still maintaining resistance to different writing instruments (e.g. fountain pen ink). The type of paper options we have today are different than the paper options we had a hundred years ago, and the same can be said for seemingly outdated writing instruments such as fountain pens. So, could I say that my laptop is more advanced than my notebooks and my pens? Well, it'd depend on what my measure to evaluate the degree of advancement is.

The thing about progress is that, ideally, we'd want to end up with more options to achieve a variety of things. Now I am not limited solely to pen and paper; I can use pen and paper and I can use other devices in which I can also write, just differently. At least in part, one of the keys of progress would seem to reside on the plurality and diversity of options, as opposed to being stuck making ends meet with the one option you have. I write on my notebooks sometimes for pleasure, sometimes to feel less constrained (pencil and paper are a great medium in which to test ideas out, draft things in a nonlinear manner, or write and draw side by side), but also because of the purely sensorial experience (e.g. touching and smelling) which contributes to my level of engagement. This is to say that, although I could do similar things digitally with a tablet, to me it just doesn't feel the same.

Should I be concerned that I am outdated, afraid of progress, or afraid of change? Should I use the newest, most advanced technology irrespective of whether I find it personally useful or not, just so that I can be in with the times? Should I jump into it head first just so that I don't run the risk of being called a technophobe?

I'd wager that choosing to use a notebook in some situations does not inherently mean that I do not know how to use other tools that (seemingly) do the same thing. I can know how a laptop works, use it in some instances and, with that knowledge at hand, decide not to use it in other instances. I can also know how a device works and choose not to use it altogether; for example, I'm privy as to how smartwatches work, but I decide not to use one because I find my smartphone intrusive as is and I do not wish to have a similar tool attached to my body. The act of choosing to use or not use a tool must not by necessity be predicated upon ignorance of the tool; in a similar vein, choosing to use a tool is not by necessity associated to knowledge of how the tool works.

Progress as a linear process

Lately, I have found myself thinking about how progress narratives are constructed when it comes to the advent of a new technology - such as generative AI -, and what these narratives mean for everything else that preceded the new technology.

Some of these narratives, it seems, conceive of progress as a linear process that brings our species to an increasingly more optimal state; we seek optimization, we seek the best option, the most efficient. For this line of thinking to work, though, one has to assume and accept the premise of "most optimal" and "best" being not only desirable states, but achievable ones. Throughout my experience teaching and supervising higher education students in the use of research methods (in my specific case, methods used in human neuroscience research), I have often encountered this line of reasoning: students seem to want to find the "one best tool" that can be used for everything and anything; the most optimal tool, the tool to rule them all. I have found myself having to deconstruct this idea (to varying degrees of success, I may add) so that we could together re-frame what a tool being optimal means; namely, a method or approach is only "the best tool" when we take into consideration what we're using it for, what our research questions are, what the problem we're trying to solve is. There is no such thing as "the best tool" for everything and anything - it'll all depend on what your needs are, what the specifics of your situation is, and on the tool's benefits and limitations in relation to the specific case at hand.

As Walt Whitman wrote in his poem Song of Myself, "I contain multitudes". Could different methods, tools, devices, and approaches coexist, or should we be forced to choose "the one" (and to choose right, because there must always be a tool that is "the best tool")? Is it an imperative for the "evolution" and "progress" of our species to only use one (ops, I mean "the best"!) option at a time? How is this process perceived by students, who are trained and supervised in a climate in which they're told they need to develop their critical thinking skills and their problem-solving abilities while, at the same time, they're reminded that they don't really have a choice and must do what their future imaginary jobs demand of them? How can we claim to have agency, to think critically, when we feel we should adopt a tool irrespective of whether it is the most useful tool for the specific task at hand?

I was recently witness to an interaction between two people on LinkedIn, in which one party (a seeming "techno-optimist") was telling the other (a teacher) that, too bad for them, their teaching job as they knew it was now obsolete and ready for extinction in the name of progress. It is (certainly?) well-known that progress cannot be stopped; you either embrace progress (whatever that is supposed to mean) or you die a little scared technophobe that is just too afraid of change - right? But how can we call ourselves progressive when we keep thinking that our existence, our choices, and our possibilities all reside in a linear, unbreakable path, instead of taking a moment to consider that having more tools may also mean having more choice? That different tools can be useful for different things at different times? And that our critical thinking and problem solving abilities are precisely to be honed through education so that we may be able to discriminate between what can be useful for one thing versus another based on our knowledge and experience?

This all means, however, that we have to live with the burden of choice, and that we should not be afraid of failing as we try to figure things out along the way. The idea that everything can be optimized, and that there is an optimal state for everything, stifles our sense of exploration, discovery, agency, and choice - and the potential for growth that arises from them - in the name of the illusion of end-game optimization.

The fear of freedom

Having to choose takes indeed time; it brings forth responsibility, it requires agency, it requires exploring and testing and figuring things out, it requires learning. The little niche of notebooks and fountain pens that I am fond of has a learning curve. In the beginning, you can't tell right from left, you may not know that fountain pens require semi-regular cleaning, that not all inks are built the same, that ink can grow mold, that using fountain pens and ink also requires considering the type of paper used, or that different paper has different properties that interact with ink and fountain pen nibs in different ways. Through exploring, trial and error, and experience, you start to see what personally works the best for you. This learning process includes instrumental aspects such as know-how knowledge, but it also brings forth a degree of self-knowledge to the user, of growth, of cognitive, behavioral, and emotional engagement with the act of learning and discovering something new, something different, which opens up the possibilities of what one can do, and what one can choose to do. The process is not just about learning how to use a tool, but about learning the why and when behind that use.

What writing in paper gives me could never be replaced by a screen and a keyboard, and I have been using screens and keyboards for the best part of the last 25 years. I have an e-reader and absolutely love it, and use it all the time; yet, I still read printed books and, for some books, I much prefer the feeling of holding them, and the haptic experience they offer, versus the experience of the e-reader. It just depends. I have my own preferences, and I feel I can make an informed choice irrespective of how novel or seemingly advanced or innovative something is perceived to be. I also pay for a music streaming service, yet I like to buy vinyls and have a vinyl player; the quality of the sound is different, and the act of choosing a vinyl, of placing it on the vinyl player, and of having to flip it when one side is over requires a higher degree of engagement and a more active role than listening to music on an app does. More novel is not inherently equal to better or more useful. It doesn't have to be either/or when it comes to tools, gadgets, or technology, and any system that forces one specific solution as the only one moving forward makes me wary of its intentions. It is a brilliant marketing tool and business approach, however; what is better than making people think they don't have a choice? If people don't have a choice, then they're users of the product by default.

Teaching and the plurality of choice

Now, when it comes to teaching, why is generative AI currently being heralded as the one and only tool and, if you don't embrace it for everything, at all times, it means you're against progress and afraid of change? Who is afraid of change here? Who is afraid of having more than one way of doing things, of giving people the choice to decide whether they need a specific tool for a specific task?

When these expectations are created (you have to use the tool just because it is the newest tool, the most advanced tool, etc.), we're creating the right environment for the uncritical adoption of technology. For example, you must have slides for presentations (does anyone at this point question whether they need them for their specific presentation or lecture, or do we use them so that we can keep ourselves aligned with what we perceive to be the attendees' expectations?). Or, alternatively, you are not working unless you have an open laptop in front of you (does anyone else feel a tad awkward when deciding to just sit and think, or to read a printed book instead?). When something becomes so pervasive, so expected, people just assume it is a given and stop critically evaluating it as a choice.

I don't use generative AI for writing, for presentations, or for visuals. The primary reason why I don't use these tools is because I simply don't feel the need. I read a lot and I write a lot and, to this day, I haven't found myself in a situation in which I've felt the need to outsource some of these tasks to a tool, irrespective of how "good" that tool may be at generating a convincing output.

I recognize, however, that the use of these tools is now so pervasive that many readers of my texts, or attendants to my talks, may just consider it as a given that the materials being presented to them contain the touch of the tool's incorporeal hand. I've started to feel a bit self-conscious about simply saying "I don't use generative AI", particularly because I often talk about these tools, I read a lot about them, and I've even written a grant proposal and hosted a workshop on the topic.

I have recently tested such a tool to explore how it could be used by students trying to improve their academic writing, as I recognize that not all students may have the option to have peer support or appropriate supervision (a can of worms of a topic for a different time). But I don't use generative AI for anything I produce myself, because it's just not something that appeals to me in any way; as hard as it can sometimes be, I find meaning in being completely engaged in the academic process and in the thinking that takes place throughout, from reading an article and being exposed to new ideas, to having to convey my own ideas to a wider audience.

Yet, I'm somehow expected to use these tools anyway, just because? Just because... why not? And if I choose not to use them, is it invariably perceived as either me being ignorant of their potential, or me being afraid of using something new? I find myself in turn wondering: why would I want to use something so uncritically? At this point, generative AI does not seem like "just a tool" any longer: it is an expectation. Sitting at your office desk with your laptop shut down and/or your PC off, eyes open or closed, does not look like working. And if I'm not visibly working, I am not being productive and efficient. If I'm not publishing as much as possible, I am not being productive and efficient. So why wouldn't I use a tool that speeds up this whole process and leads to visible outputs that can in turn be easily quantified as proof of my working capacity? Because what is the opposite to being productive and efficient, other than simply being a shit lazy worker?

I cannot visibly show I am thinking, but I'd claim that there is a lot of thinking that needs to happen in an academic job. If I sit at a café, alone, with a book, am I working? How much time can I effectively dedicate to thinking, and where should this happen? If I'm taking a shower and mentally going through the flow of a script for a presentation I'm giving, am I working? Have we come to expect that working these type of jobs requires, necessitates, that works happens at all times through a keyboard and a screen? That I should use any tool at my disposal that visibly shows that I do in fact work, preferably at the highest speed possible? Have we come to think about all jobs as factory jobs in which the speed at which things are produced is a direct indication of how efficient work is? In my experience, these expectations take us away from what is actually useful for the tasks at hand and from the informed, evidence-based, critical process required to choose the most optimal way to achieve our very specific goals. Instead, they convince us that our collective goal is to solve problems we didn't know we had (being more productive, being more efficient) by the use of the one and only, universally optimal tool, to the benefit of the few that seem to hold the key to humanity's ever-elusive "end-game progress".

What if the line is actually a tree?

There are many things that I consider worth saying when it comes to the place of generative AI tools in academia. For one, I think that the field is losing sight of what reading and writing (and, in some cases, coding) entails; what it is that happens in the processes of reading and writing that cannot just be simply outsourced to a tool, and how we understand the generation of knowledge and the quality of thinking and reasoning needed to get there. Here, however, I chose to focus on the act of choosing, and how the ability to discern what is needed and to choose accordingly grows from the soil of critical thinking. We cannot hold critical thinking skills in a high regard while, at the same time, we expect and reinforce the uncritical, "no questions asked" use of technology.

When we're saying things like "progress cannot be stopped" and "the tasks / tools that preceded the advent of this technology are now de facto outdated and unnecessary", we need to understand that we're stuck in a linear way of seeing something that is by no means linear. It is the reasoning equivalent of sticking to the idea that evolution is a linear process when it is certainly not. Progress does not happen in a linear way, but in a multidimensional branching way. Multiple things (tools, approaches, ways of thinking and understanding) are happening at the same time, existing within the same timeline, and progressing down their own lanes. These lanes, in turn, are so qualitatively different that they cannot be measured through purely quantitative means as "better" or "worse". The scale seemingly being used to measure progress doesn't in fact exist, and deciding that the one true most optimal best tool is now the only choice is the opposite of progressive; it fails to acknowledge that a tool on its own is meaningless unless its case use has been considered, and its case use cannot in practice be "everything and anything".

So, no, teachers are not obsolete just because a novel tool that mimics human language has been introduced to the market. No tool has to be used just because it is here and it is new with no further critical inquiry. No tool, no matter how advanced it is touted to be, must be implemented and used in the name of progress with no choice being offered, and this is particularly the case in instances for which there is no real need for it. New tools, just as fancy new toys, can be there to be explored and played with (as long as this doesn't involve the discrimination and exploitation of massive groups in society, right?), but they should never be imposed onto us with no questions asked. We cannot claim to be in the field of thinking and of teaching others how to think if we're not willing to critically think about this and to be ready to make an informed choice in the matter.